Biopowered Ascites Shunt

The Problem

Cirrhosis of the liver is often accompanied by refractory ascites, defined as fluid buildup in the peritoneal cavity that does not recede or recurs shortly after therapeutic paracentesis (removal of ascites fluid) [1]. The condition leads to significant patient discomfort and has a 1-year survival rate of approximately 50% [1].

In addition to the clinical burden, the total procedure related cost of paracentesis is estimated at $24,755 per patient per year in the United States, and there are over 150,000 such procedures performed each year in the US alone [2][3].

Currently, there is no effective therapy for refractory ascites, although several management strategies have been used:

- Large Volume Paracentesis - an expensive procedure (~$13,000 per case) which requires surgical puncture of the abdomen [2, 3].

- Peritoneovenous Shunting - rarely performed due to risk of infection, leakage of ascitic fluid, edema, coagulopathy, and shunt blocking.

- Transjugular Intrahepatic Portosystemic Shunts (TIPS) - a procedure associated with increased risk of hepatic complications and no clear improvement in survival [4, 5].

- Liver Transplant - only considered for extreme cases of ascites, however availability is limited and the procedure is extremely expensive.

Solution

Our solution was an implantable passive pump, powered by the natural pressure fluctuations in the body from breathing. The pump consists of two compartments: a fluid-shunting compartment and a sealed, compressible fluid chamber.

The fluid-shunting compartment is attached to two lines: a collection tube with a perforated proximal end situated in the peritoneal cavity where ascites collects, and a drain tube with its distal end situated within the bladder. Each line is connected to the pump with one-way valves to prevent backflow into the peritoneal cavity and to increase fluid flow to the bladder. The compressible fluid chamber is sealed from the shunting compartment by a thin, flexible silicone membrane.

Research has shown that there is no significant pressure gradient between the peritoneal cavity and the bladder at various degrees of ascites. Therefore, it is assumed that the pressures at the inlet and outlet of the pump are equal to the intra-abdominal pressure (IAP) at all times.

- During steady state conditions, the internal pressure of the pump is equal to IAP.

- As IAP increases, the pressure gradient across the one-way inlet valve increases and allows fluid to enter the pump. The elastomeric membrane stretches, which produces an equal and opposite force that raises the pressure in the fluid compartment.

- As IAP decreases, the pressure gradient across the inlet valve falls and is not sufficient to keep it open.

- As IAP keeps falling, the pressure gradient across the outlet valve increases, allowing it to open and expel fluid from the pump. A vital design consideration is the opening pressures of the one-way valves.

- MRI compatible (patients in the late stages of the disease need to be visualized under MRI).

- Low cost of device & implantation: no electronic components coupled with the fact that the device can be implanted in an outpatient setting under conscious sedation, which does not require expensive operating room time and resources.

- Ease of placement: well established placement methods for tunneled peritoneal and suprapubic catheters, so physicians would be comfortable with the proposed hybrid approach.

- Decreased infection risk: the closed-loop drainage system created by the PeriLeve device significantly reduces the risk of introducing external infection. [1, 4].

- Eliminates the need for hospital or clinic visits for paracentesis as patients can manage their refractory ascites at home, thereby improving their quality of life.

Vacuum formed hemispheres were initially created; however, sealing the halves together with a feasible membrane was difficult. Thin, rubber sheets were the only viable membranes able to be sandwiched between the two halves, but these membranes were not stiff enough to build up a sufficient internal pump pressure.

A silicone body was then considered by creating the two halves from a plastic mold. The advantage here was that the patient could manually compress the pump body to drain fluid, as the pump was a subdermal implant.

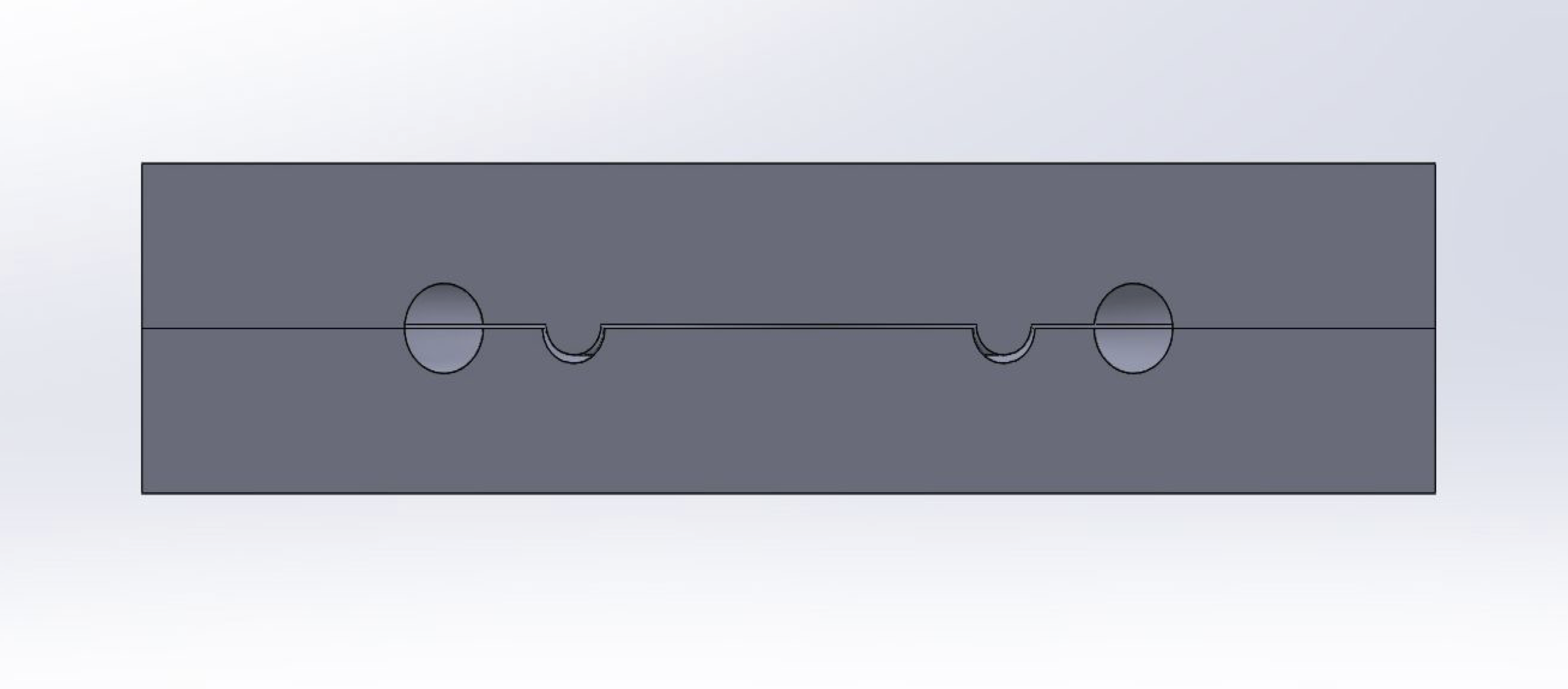

A 3D printed iteration was lastly developed to isolate the impact of internal pressure fluctuation on fluid movement, as the patient would not be able to physically compress the pump. The pump was assembled via a thread running along its circumference; a membrane was placed in the bottom half, after which the top half was screwed into place.

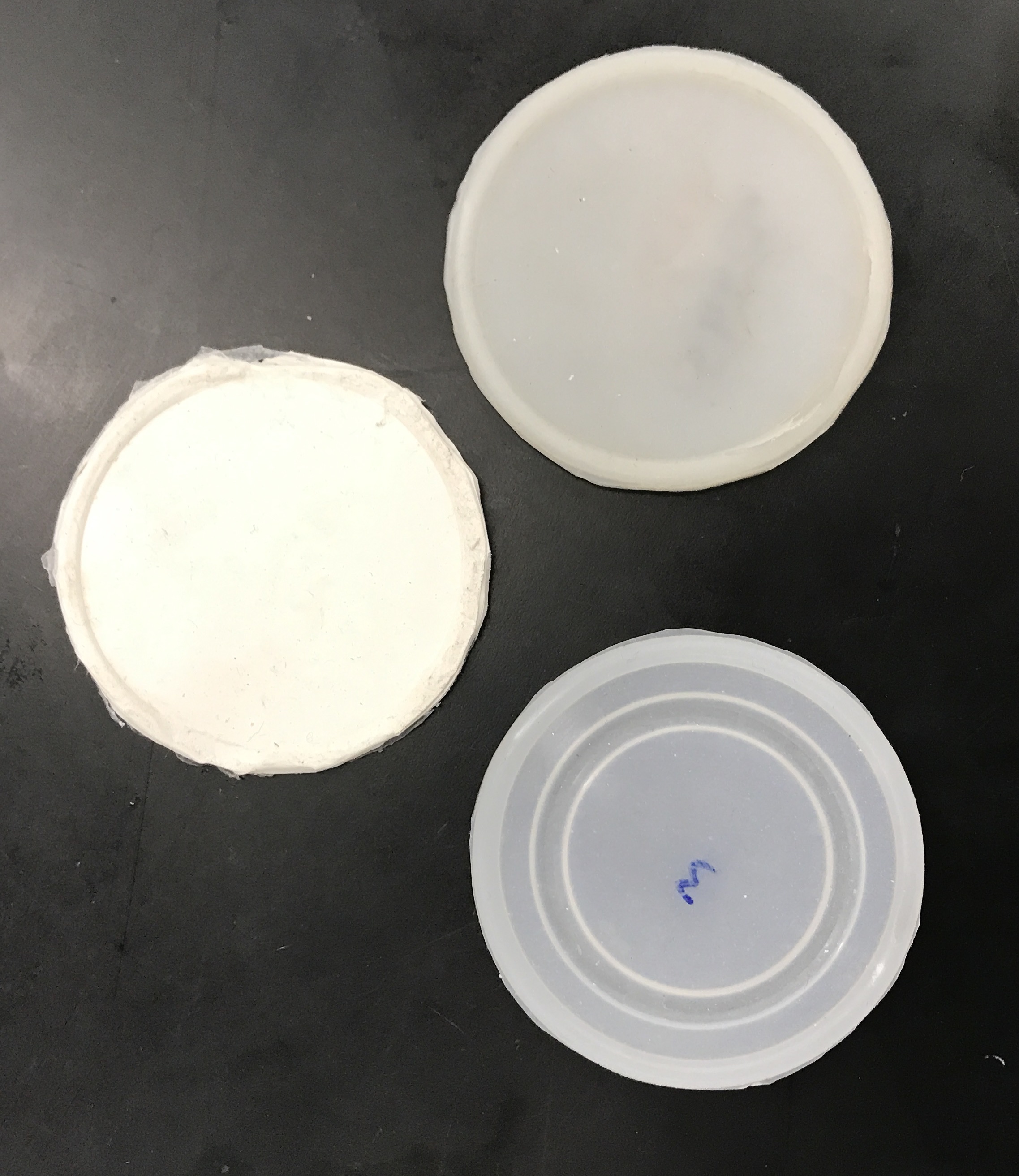

Various methods were utilized to create the elastomeric membrane.

- Spin casting was implemented first; however, it was difficult to achieve an accurate and consistent thickness.

- Silicone was then cured in plastic molds; however, the process was inefficient and inconsistent. Despite the use of a vacuum prior to curing the membranes, air bubbles were always found in the end result.

- Vulcanization was then used, which allowed the membrane to be fabricated quickly and consistently. Aluminum machined molds allowed for the high heat and pressure required for vulcanization.

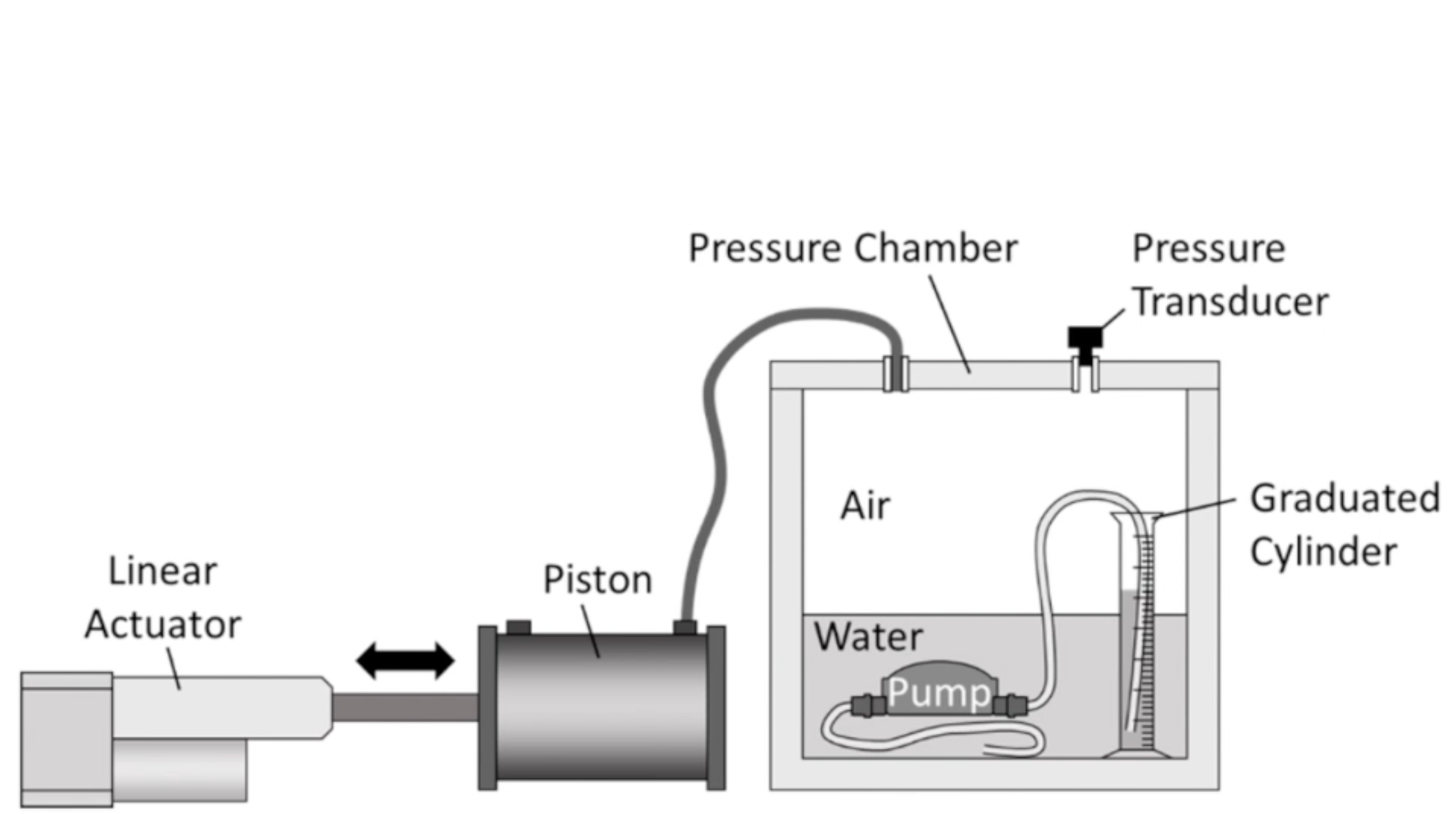

An in-vitro model was created in order to test the peritoneal vesicular pump. The model acts as a pressure chamber that can be programmed to pressurize/depressurize to a certain pressure using an Arduino.

As pressure within the chamber increases, fluid is drawn into the pump. Similarly, as pressure drops, fluid is moved out of the pump. Changes in intra-abdominal pressure due to breathing can be modeled with a sinusoid, and so the bench top model was programmed with this in mind.

The performance of the pump has been characterized for several pressure thresholds that are representative of in situ fluctuations (5, 25, 40, 80 cm H2O to simulate breathing, walking, normal cough, and high cough, respectively) [6, 7]. The minimum operating pressure of the pump was found to be 25 cm H2O, indicating that the pump in its current state should work as the patient walks.

For this, we had to devise a new method to simulate refractory ascites physiology and measure the amount of fluid shunted from the peritoneal cavity into the bladder.

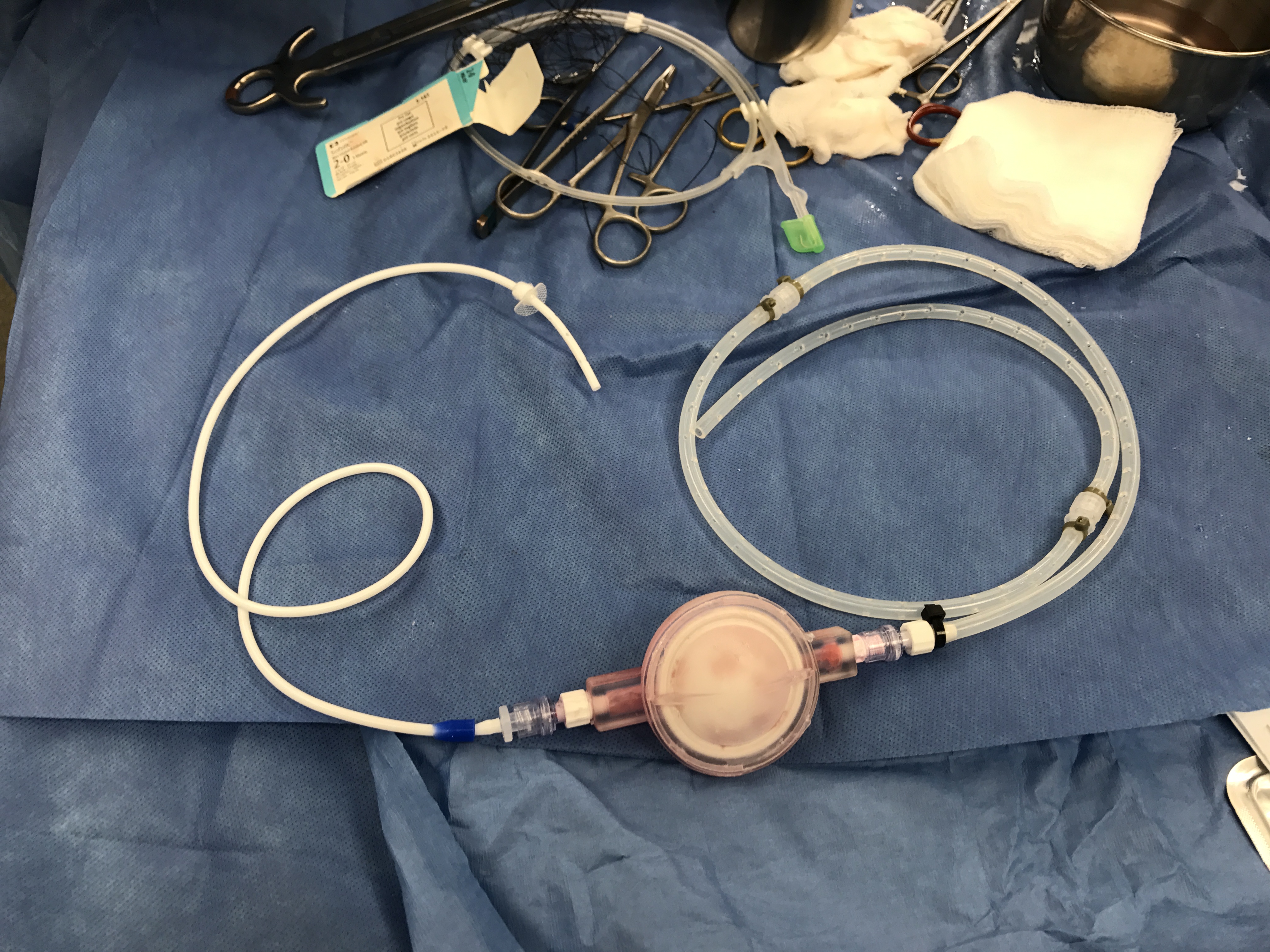

Via laparotomy, we created an anuric model by ligating the ureters and implanted the pump secured in a subcutaneous pocket. Large volumes of dialysis fluids were instilled daily into the peritoneal cavity to simulate ascites. The pigs were monitored closely and the bladder fluid was collected and measured over several days via a Foley catheter placed in the bladder.

Further optimization is required, but initial results show that fluid can be shunted from the peritoneal cavity to the bladder.

- Siqueira, Fabiolla, Traci Kelly, and Sammy Saab. "Refractory ascites: pathogenesis, clinical impact, and management." Gastroenterology & Hepatology 5.9 (2009): 647.

- El Khoury, Antoine C., et al. "Economic burden of hepatitis C-associated diseases in the United States." Journal of viral hepatitis 19.3 (2012): 153-160.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. HCUPnet. US Department of Health & Human Services. 2012 National Statistics – principal procedure only. http://hcupnet.ahrq.gov/HCUPnet.jsp

- Salerno, Francesco, et al. "Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt for refractory ascites: a meta- analysis of individual patient data." Gastroenterology 133.3 (2007): 825-834.

- Deltenre, P., et al. "Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt in refractory ascites: a meta-analysis." Liver International 25.2 (2005): 349-356.

- Hodges, Paul W., and Simon C. Gandevia. "Changes in intra-abdominal pressure during postural and respiratory activation of the human diaphragm." Journal of applied Physiology 89.3 (2000): 967-976.

- Moore, K P, and G P Aithal. “Guidelines on the Management of Ascites in Cirrhosis.” Gut 55.Suppl 6 (2006): vi1–vi12. PMC. Web. 14 Jan. 2016.