Microgravity Cell Culture Environment

The study of cells in microgravity environments is imperative to future space endeavors. Currently, the best method is to send cells to space and analyze their growth. However, this is extremely expensive and is rife with logistical issues. Therefore, microgravity environments have been simulated, mostly focusing on devices that rotate in one or two axes.

Cell samples are rotated to prevent the biological system from feeling the gravitational acceleration vector, rotating at a slow 0.3-3 RPM to avoid any centrifugal effects. These systems rotate with an axis perpendicular to the gravitational acceleration vector, which allows the sample to feel an approximate weightless environment as the gravitational pull is averaged over 360 degrees.

The Problem

The Lab of Mechanochemistry and Functional Imaging Applications at Johns Hopkins University under Professor Yun Chen has purchased its own microgravity simulator. The original device allows for one batch of cells to be placed in the microgravity environment at a time. A slide is rotated at a steady rate of 3 RPM by a stepper motor that is housed in the glass casing.

While this design can successfully simulate microgravity, there are several areas of improvement:

- Only one batch of cells can be grown at a time.

- The device requires extensive effort to disassemble.

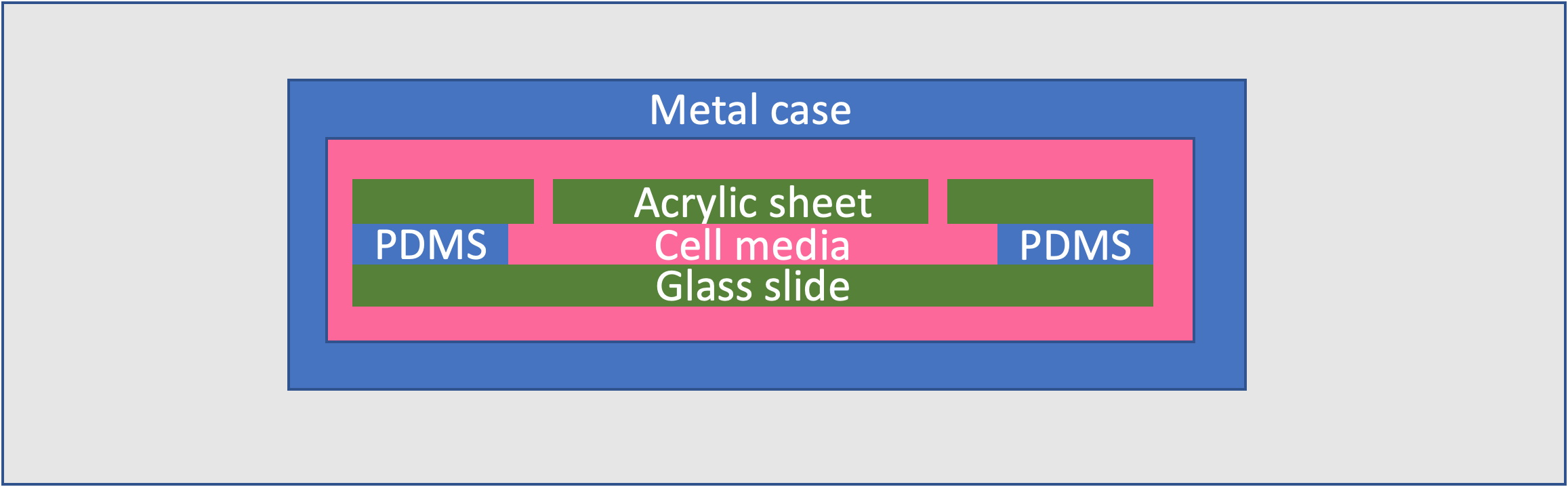

- The method of medium replacement is not efficient. The cells sit in a channel of Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS), which must be tediously remade for every new batch in order to avoid contamination.

- This PDMS channel is held in the slide by a steel casing, which rusts.

- The entire device must be placed in an incubator to keep the cells at the appropriate temperature (37° C).

- The device is costly ($2,000).

Solution

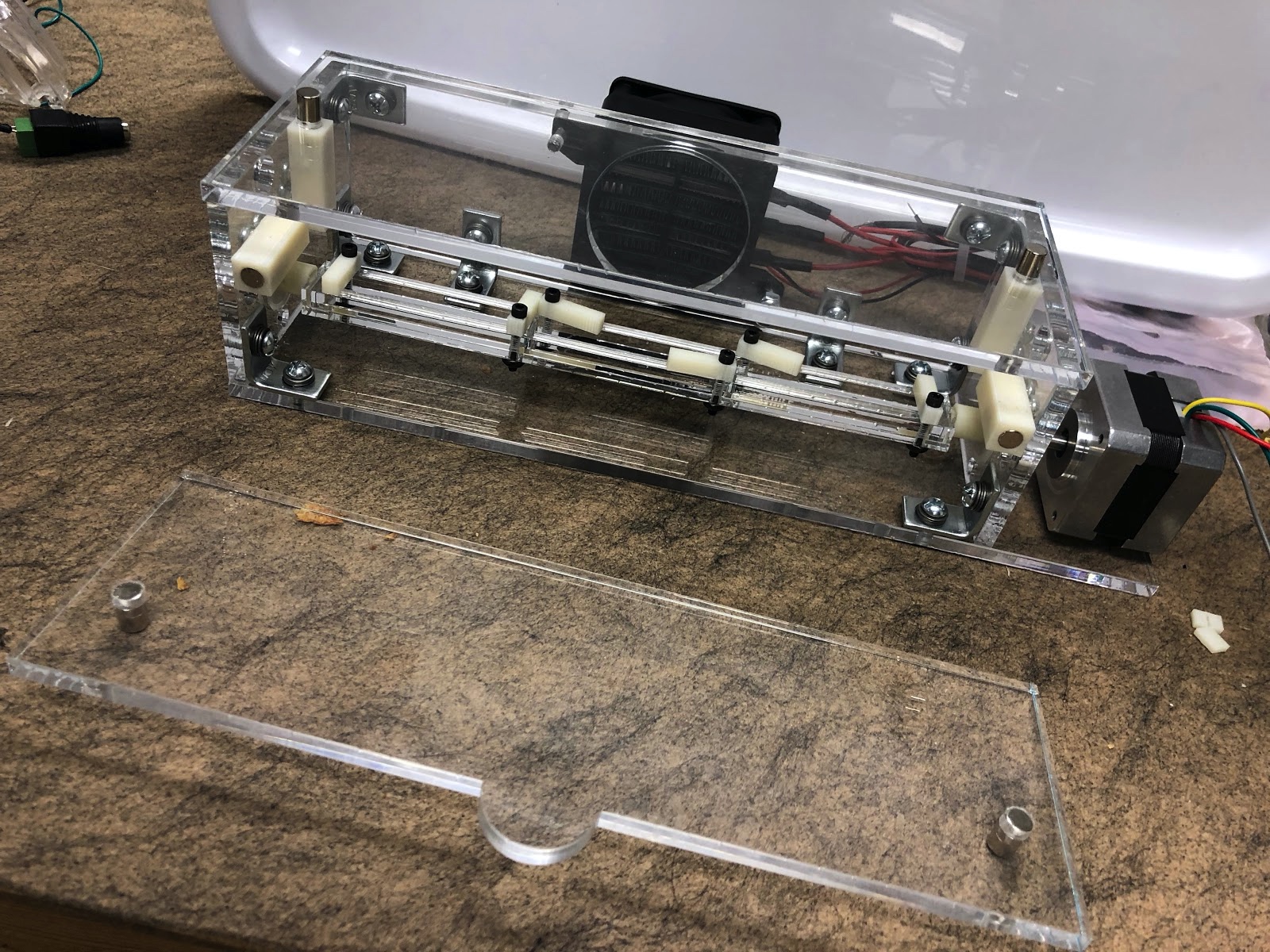

Our solution consists of an acrylic sheet housing, a heater, a stepper motor, and a rotating slide deck that can hold three slides. It also consists of a user interface, which includes a Raspberry Pi and touchscreen. All together, the components cost $270 (compared to the original device cost of $2,000).

The device is housed in an acrylic casing with a heater to keep the cells at the right temperature, eliminating the need for a separate incubator. Magnets hold together the housing walls, allowing the system to be disassembled quickly. The slide deck can hold three different slides and has latches that swivel to enable easy replacement of the individual slides.

We replaced the previous slides with 3D printed ABS ones, avoiding the risk of rust and allowing the slides to be recreated very easily for each new batch of cells. The channel is then formed entirely out of PDMS inside this slide, instead of covering the top and bottom of the cell channel with acrylic. The type of PDMS used is a Sylgard 184 Silicone Elastomer Kit.

To form the slides:

- Insert a small rectangular piece of 0.5mm brass shim stock through the needle insertion points and place the slide in a Petri dish.

- Pour the Sylgard 184 into the center of the slides and allow it to overflow and cure.

- After the PDMS has cured, the user should remove the brass negative with tweezers and cut away any excess PDMS.

We programmed a Raspberry Pi/touchscreen interface that allows for the user to choose the rotational speed of the cells. The method of medium replacement is also expedited, as users can easily remove the slide from the deck and insert new medium through the needle insertion points. Miniature valves were added to the slides to contain the medium and cells during rotation and to prevent contamination.

To use the device, the slides must first be printed and formed as described above. To load the cells and medium, the user should use a 1 mL syringe with a 26G needle. The user can then place the slides into the device and select the desired experiment parameters using the interface.

We grew cells for 18 hours in the device to demonstrate its efficacy in simulating microgravity environments to cultivate cells. The images were taken from a bench-top microscope at 10X and 20X magnification.

The average cell size was 25 micrometers. The cells exhibited a similar morphology when cultured on a substrate with similar stiffness as the PDMS stiffness (1.3~2 MPa). From our study, we concluded that our device simulates the microenvironment of the traditional cell culture and is viable for the study of cells under microgravity conditions.

Another technical challenge with the current solutions to microgravity simulation is imaging. Primarily, it is difficult to continually image cells in microgravity conditions to study how they change over time. Taking cells out of the device to study them under a microscope will return them to normal gravity conditions and interferes with the experiment. This also means that the cells can only be imaged once a day to mitigate the effects of this environment change.

Our next step is to implement a track and microscope system that can image cells at a desired frequency. Once configured to the right distance from the cells, the microscope will take pictures of the cells at a much higher frequency without having to remove the cells from the device. The track will be able to move the microscope along the horizontal axis to image the cells in all three slides.

- Robertson, C. and Kim, I. H., Biotechnol. Bioeng. XXVII pp. 1012-1020 (1985).

- Raul Herranz, Ralf Anken, Johannes Boonstra, Markus Braun, Ground-Based Facilities for Simulation of Microgravity